Want to stay informed about the Bombing of Darwin commemoration?

Sign up to receive updates straight to your inbox. Click here to subscribe!

Event Livestream

On 19 February 1942 Darwin was bombed by enemy forces becoming the largest single attack ever mounted by a foreign power on Australia.

The attack left hundreds of servicemen and civilians dead, and countless others injured.

Each year we come together as a city and a nation, to pay tribute to the men and women who were there.

2026 Bombing of Darwin Day Commemorations

On the 19th of February each year, we commemorate the Anniversary of the Bombing of Darwin.

In 2026, it will be 84 years ago that Australia faced an unprecedented foreign attack on home soil.

In 2011, Bombing of Darwin Day joined Anzac Day and Remembrance Day as a National Day of Observance.

The Bombing of Darwin Day is a day to reflect on our past and to pay tribute to those servicemen, servicewomen and civilians who were there - those who courageously defended our country, those who selflessly helped others, those who dealt with the aftermath, and of course, those who lost their lives.

The 19th of February 1942 marked the first of at least 64 air raids on the Top End of Australia, which continued for 18 months, until November 1943. In commemorating this day we are also passing the story on to the next generation.

On Bombing of Darwin Day, we remember and commemorate all those who were part of the war fought over Northern Australia

City of Darwin is pleased to present The Bombing of Darwin Day Commemoration and invites you to join us at the 84th Anniversary Commemoration Service on 19 February 2026 which will be live streamed.

Event details:

Bombing of Darwin Commemorative Service

Thursday 19 February 2026

Darwin Cenotaph, The Esplanade, Darwin

9:30 am – 11:00 am

Public safety plan

- USS Peary Memorial Service - 19 February, 8:00 am - 8:45 am

-

Date: Thursday19 February, 2026

Time: 8:00 am - 8.45 am

Event: USS Peary Memorial Service

Venue: USS Peary Memorial, Bicentennial Park (between Daly St and Peel St area)

Host: Australian American Association NT

Booking and contact information: Free, open to the public

- Bombing of Darwin Commemorative Service - 19 February, 9:30 am - 11:00 am

-

Date: Thursday 19 February 2026

Time: 9:30 am - 11:00 am

Event: Bombing of Darwin Commemorative Service

Venue: Darwin Cenotaph, The Esplanade, Darwin

Host: City of Darwin

Booking and contact information: Free, open to the public. For more information, contact darwin@darwin.nt.gov.au (08) 8930 0300.

- Watch Event Livestream

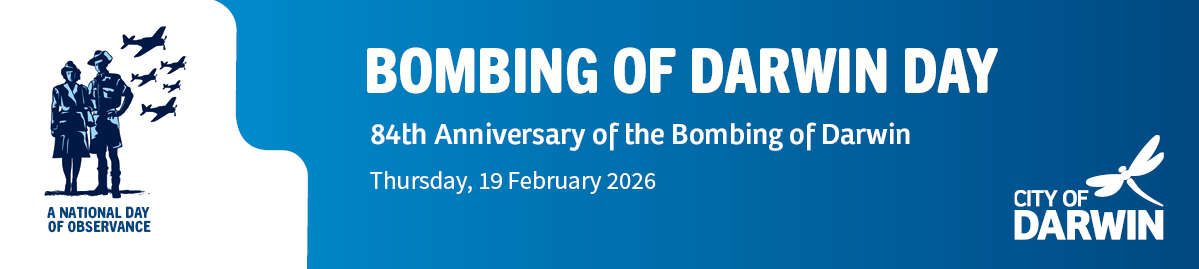

- Important event road closures and traffic information

-

City of Darwin wishes to advise that parts of the Esplanade will be closed for the USS Peary commemorative services.

No access

The Esplanade will be closed between Daly Street and Peel Street from 7:30 am to 9:15 am, and Herbert Street and Knuckey Street from 8:00 am to 12:00 pm.

The Esplanade between Smith Street and Herbert Street, and Herbert Street itself will be closed from 10:45 am to 11:30 am.

Limited access

Access for the Herbert Street State Square Car Park entry and exit will be maintained off Mitchell Street during this time.

Oval Carpark access by pre-approved entry pass only via Herbert Street.

- Bombing of Darwin Ecumenical Service - Thursday 20 February, 10:00 am - 11:00 am

-

Date: 20th February 2026

Time: 10:00am

Event: Bombing of Darwin Ecumenical Service

Venue: Adelaide River War Graves, Civilian Section

Host: Coomalie Community Government Council

Booking and Contact info: Bookings on 8976-0058, contact Andrew Roberts for further information

The human experience - stories of war in Darwin

- 1. Women in Wartime Darwin

-

From evacuation orders to active service, the women of the Northern Territory contributed to the war effort in the north in a multitude of ways.

Prime Minister Robert Menzies gave evacuation orders shortly after Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbour, late in 1941, that required all women and children to compulsorily leave Darwin. Many women didn’t want to leave, but most were hoarded together and loaded onto coastal steamers, sometimes against their will, for their uncomfortable journeys to the southern states. In all, over 2000 women and children were evacuated, many never returned.

Some women managed to stay however, claiming essential jobs such as secretaries, nurses, court stenographers, maids and telephonists. When the first bombs fell on Darwin there were approximately seventy women left, including Aboriginal, Chinese and European women.

Sadly, among them were the wife and daughter of the Postmaster along with his team of female telephonists who died alongside the Postmaster and several male members of staff when their air-raid shelter suffered a direct hit during the first air-raid on 19 February 1942. Nearby, an Aboriginal woman, Daisy Martin, a member of staff at Government House was also killed in those first attacks.

Large numbers of army nurses and enlisted women served in military hospitals and camps throughout the Territory, including nurses based in Darwin from mid-1941. They tended many wounded on 19 February 1942, some working continuously for up to 48 hours, and were described as heroines - alongside all the women in Darwin that day.

Other women stayed in the Northern Territory by moving south, from Darwin, to work alongside men in military outposts and townships up and down the ‘The Track’ providing crucial support throughout the war. In places like Tennant Creek organisations like the Country Women’s Association handed out thousands of loaves of bread, cakes and tea to convoys of troops passing through, and hundreds of Aboriginal women provided vital labour at army installations and medical facilities.

One such woman was Larrakia woman, Dolly Gurinyi Batcho, who was given the unofficial rank of 'corporal', leading the unofficial Aboriginal Women's Hygiene Squad at the barracks at Adelaide River. Unglamorous and hard work, their job was to maintain the cleanliness and sanitation of the camp, and although essential, none of the women enjoyed the benefits of formal enlistment or recognition.

(Nurses used bikes to cycle to and from duty. Northern Territory Library Darwin.)

- 2. Unsung Heroes - The Aboriginal & Tiwi Experience

-

Aboriginal people played a significant, although largely unrecognised, role in the defence of Northern Australia during World War II. It’s only in recent years that the many heroic deeds and essential service that Aboriginal gave to the war effort are finally being acknowledged.

A rifle platoon of around 40 Aboriginal men were attached to the Darwin Mobile Unit, and were colloquially known as Darwin’s Black Watch. They trained hard and soon reached a high level of military efficiency. They were also highly skilled in tracking and survival, rescuing countless American airmen who were shot down in remote places like Arnhem Land in battles with Japanese air-craft

The Tiwi Islands was home to a squad of locals who unofficially enlisted in a Navy unit that became known as the Snake Bay Patrol. Located on the critical path of Japanese air-craft headed for Darwin, the unit was responsible for special duties such as locating stranded airmen and Japanese mines. Despite not having formal authority to form the unit, they achieved extraordinary military efficiency, wore uniforms and were proficient in parade ground and small arms. Tiwi Islander Matthius Ulunguru tracked a crashed Japanese pilot who became Australia's first POW, capturing him with the words “Stick ‘em up, right up”!

Another irregular unit that supported the war effort was the North Australian Observer Unit, otherwise known as the Nackeroos. This unit was mobile, usually on horses rather than vehicles, and lived for long periods off the land operating in small groups throughout Northern Australia and further afield. Around 50 Aboriginal men worked directly with the Nackeroos, providing food, guidance, tracking, labour and horse handling skills.

In Arnhem Land, the army trained about 50 Yolngu men to defend their coastline. This unit, based in East Arnhem Land, patrolled using traditional weapons and fought guerilla style warfare. They were known as The Northern Territory Special Reconnaissance Unit and many non-Aboriginal service men and people who lived in these remote areas relied on their skills for survival.

These are just some of the examples of how Aboriginal people contributed to the war effort, but there are many more stories including the efforts of men and women who worked as medics, orderlies, cooks, spotters, ammunition handlers, engineer assistants, ship’s crew and more. They were mostly paid in rations or tobacco, despite the vital support they provided to the war effort.

(Members of the 2/18th Field Workshop in Tennant Creek in 1942. All except two of the men pictured are Indigenous Territorians. Northern Territory Library Darwin.)

- 3. A Larrakia Story - Juma and Samuel ‘Smiler’ Fejo

-

“Grandfather Juma and Grandfather Smiler both had nightmares of blood, gore, oil and fire”, explains Larrakia woman Christine Fejo-King. “They spoke about getting to the injured men first, to pull them from the water, and then going back for the dead”.

Juma Fejo was a corporal cook on Larrakia Hill the day all hell broke loose on Darwin Harbour, on 19 February 1942. But he wasn’t worried about himself, his thoughts were with his younger brother Samuel Fejo, who was a gunner located down on the wharf. “As soon as the bombs started to fall Grandfather Juma ran down to the wharf in search of his brother Samuel, who everyone called ‘Smiler’ because he had these big dimples”, smiles Ms Fejo-King.

Juma Fejo found Smiler just as the gunner ran out of ammunition, so the two men ran down to the water and started to swim through the muck and fire to rescue whomever they could. When they could find no-one else alive, they started to pull dead bodies out of the water and line them up on a small stretch of sandy beach near Stokes Hill Wharf.

The 19 February was just one horrific day, in what was a long war for the Fejo family, but a day that both brothers thankfully survived. The men were also part of a militia group, known colloquially as Darwin’s Black Watch. Made up almost entirely of Aboriginal men, the Black Watch were adept at surveillance and rescue. Their supreme survival and bush skills, combined with their excellent tracking capabilities, saw them used for search and rescue operations throughout Northern Australia.

At the time, American and Japanese air-craft were in battle over remote parts of Arnhem Land, and the skills of the Black Watch men were called upon numerous times to locate crashed American airmen.

“Years after the war, one of these rescued American airmen came back”, tells Ms Fejo-King. “He couldn’t remember my Grandfather Juma’s name, because it’s so unusual, but he could remember Samuel’s name’. He put a notice in the old newspaper, saying that he was looking for Samuel Fejo, and that he would wait at the Hotel Darwin”.

“My mother Lorna Fejo, was chosen to go and meet with the American airman. She was understandably apprehensive but was happy she went when he explained that he was searching for Samuel and Juma to thank them for saving his life”, explains Ms Fejo-King. “She sadly had to tell him that both men had passed away since the end of the war. She would often recall that it was the first time she had seen a white man shed tears over the death of an Aboriginal person.”

A Bombing of Darwin Remembrance and Reconciliation Activity is being held near the USS Peary Memorial on The Esplanade on 19 February 2022, between 1:30 - 3pm. The event will mark the 80 years that have passed since the bombs first fell on Darwin, crushing Larrakia land and spilling blood and oil throughout Larrakia waters. Everyone in the Darwin community is welcome and are encouraged to bring family stories, an open heart and a listening ear to pay tribute to all who served in Northern Australia during WWII. Stories will be shared by the descendants of both Darwin’s Black Watch and other service personnel who defended Darwin during the bombings and other attacks during WWII.

“In our culture, if you save someone’s life, the connection will remain as long as the story is still told”, explained Ms Fejo-King. “It’s serendipity that we are holding a storytelling event overlooking the USS Peary memorial, which is in honour of the many Americans who lost their lives when their ship was bombed. We have a connection with the Americans through my grandfathers, and the other Black Watch men, who saved many of their airmen during the war, and we will continue to tell the stories and keep the connection alive”.

(Christine Fejo-King holding portraits of Juma Fejo and his wife Kathleen Kitty Stewart, and Samuel ‘Smiler’ Fejo.)

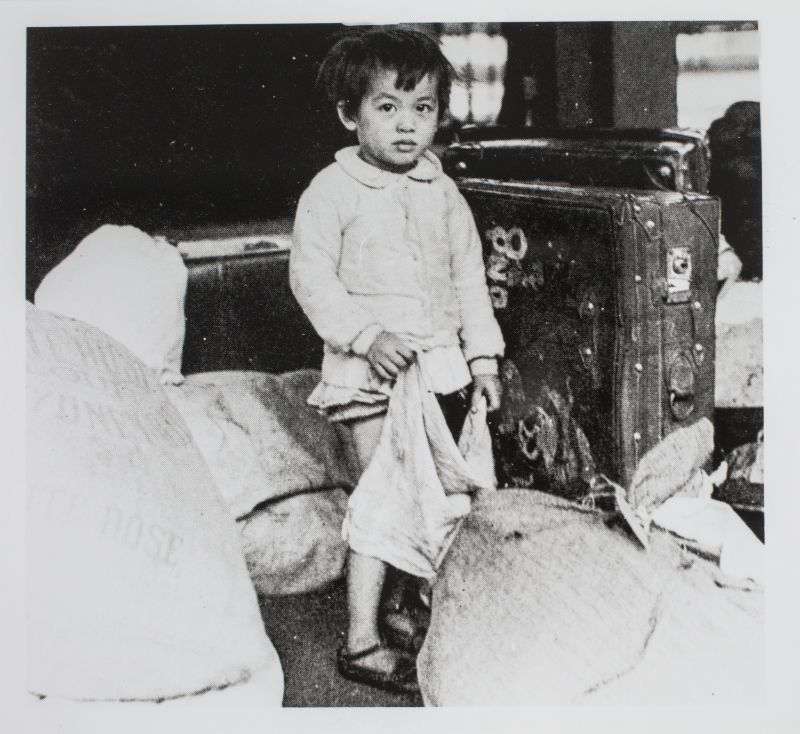

- 4. Sweet and Sour - The Chinese Experience

-

Before WWII, Darwin’s Chinatown was a bustling, thriving community full of merchants, tailors, market gardeners, pig breeders, store keepers, bakers and launderers. All that changed when war came to Darwin, and it would never be the same again.

On the 20th of December 1941, knowing that war was close, the ship Zealandia evacuated 530 people from Darwin, including 206 Chinese women and children. It was no pleasure cruise. On their way to Sydney, the Chinese were largely confined to the open deck area, with no fresh food, and limited toilet and washing facilities. Many would never return to Darwin.

For those in the Chinese community that stayed in Darwin, many joined the armed forces and served in a variety of roles, from cooks to soldiers. For Herbert Wong, after he joined the infantry in Adelaide River, his division was moved to Darwin. When the army was seeking volunteers in the kitchen, he put his hand up. The troops enjoyed his cooking so much he became chief cook at the headquarters of Major General Murray at Myilly Point. Herbert Wong would obtain the ranking of Corporal.

Newlywed Ernest Fong was in Katherine when the first attack happened in Darwin. All his possessions, including wedding presents, were back at his home there. He managed to travel back to Darwin a week after, and he recalls the devastation he saw.

“I remember the wreckage and shambles and the dead silence in town. The silence was frightening, worse than anything else. The dead silence and nobody around was eerie - dead - I went around to the Esplanade, the Police Station and there was nobody. There weren’t even any animals around, you could have fired a cannon around and not hit anyone. Our place was not bombed. At that stage, the rest of Chinatown was alright.”

Six members of the Darwin Moo family served in the armed forces. Harry, Clarence and Arthur Moo joined the Air Force. Joining was not easy, as the Defence Forces generally wouldn’t allow persons of non European descent to enlist. Arthur Moo recalls his boss, the Postmaster Mr Ball saying, “You can work for the Government, pay taxes and when you turn 21 you can vote, why can’t you die for your country?”

Following war’s end many Chinese evacuees returned to pick up where they had left off, however the Chinatown they knew was nowhere to be seen. With bomb damage, and the army demolishing buildings and looting, it was mostly just dust and memories. Sue Wah Chin’s stone houses and the Don Hotel were all that remained.

Chinese civilians and military alike helped in any way they could with the massive clean up.

(Darwin child evacuee, Nellie Fong, 1942. Northern Territory Library Darwin.)

- 5. A Mighty Job - Defending Darwin

-

Darwin had been a strategic port on Australia’s northern edge for decades, but in the mid-1930s a major military build-up began. By 1942, the population had more than tripled, with around 7,500 troops stationed in Darwin and many military installations dotted throughout the Territory.

After recruiting men from around Australia, the Darwin Mobile Force arrived in Darwin on 29 March 1939 and took up residence. With both infantry and artillery elements, they trained hard in the harsh conditions and became a resilient and tight-knit fighting force.

After Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941, there was a growing realisation that an attack on Darwin was imminent. Over 2000 women and children were evacuated from the region by air, road and sea. The final evacuation aircraft left Darwin just one day before the first Japanese air raid. There were, however, around 2,300 civilians still in Darwin on 19 February 1942.

Just before 10am that day, World War II forced itself onto Australia’s mainland for the first time, when formations of 188 Japanese aircraft mounted a deadly air raid on Darwin and the terrible sound of whistling bombs rang in the ears of allied troops and civillians alike.

Bombs rained down on Darwin city and direct hits were suffered by the Darwin Post Office, killing the post-master, his family and 6 female telegraphists, and the nearby residence of the Administrator, killing a young Aboriginal woman who was working for the family.

Allied aircraft mounted a counter-attack and gallant anti-aircraft gunners fought to protect the City and Harbour, but sadly, by the day’s end at least 235 people were killed, more than 400 were wounded, 30 aircraft were destroyed, 9 ships were sunk and many civilian and military facilities were damaged.

On the 19 February 1942, Darwin Harbour was dotted with 46 allied ships which became targets for the enemy aircraft and soon black smoke rose from damaged ships. Burning fuel on the surface of the Harbour’s water created a deadly hazard for survivors trying to escape the carnage.

The Neptuna, an ammunition ship, was tied up at the Wharf, and nearby the destroyer USS Peary was anchored, having arrived back into Darwin Harbour that morning for supplies. A direct hit to the wharf killed at least 21 wharfies, and both the Neptuna and Peary were bombed multiple times, and sunk to the seafloor. Around 24 men on board the Neptuna and up to 92 men on the USS Peary lost their lives that day.

Between February 1942 and November 1943, Darwin was bombed at least 64 times. None of the subsequent raids matched the ferocity, and didn’t incur the same amount of damage and deaths, as did the air raids on that first fateful day.

(Soldiers defending Darwin. Northern Territory Library Darwin.)

- 6. Then and Now - what do Australian’s know about the Bombing of Darwin?

-

The Bombing of Darwin is often referred to as Australia's Pearl Harbour. In fact, the attack on Darwin was led by the same Commander Mitsuo Fuchida, who led the Japanese raid on Pearl Harbour.

Yet, while the world remembers Pearl Harbour, many Australians don't know a lot about the 19 February 1942, when Darwin's skies were darkened by Japanese aircraft and the whistling of bombs rang in the ears of those on the ground and in the Harbour.

So why did one event capture the world's attention, and not the other?

- It's likely that the devastation at Pearl Harbour, just 3 months prior, overshadowed the attacks on Darwin. There were 2,388 lives lost in the Pearl Harbour raids compared to around 235 killed in Darwin. Also, whilst there were more bombs dropped on Darwin Harbour and more ships sunk, the bombs were much smaller in size and the tonnage sunk (the size of the ships) in Pearl Harbour was much greater.

- The attacks on Darwin were downplayed to the rest of the Australian public. The number of people killed and injured were initially reported as much lower and the amount of damage inflicted on our city was considerably understated. It is thought that the under-reporting was both tactical, for national security reasons, and logistical, the authorities and media just didn't know about the extent of the devastation until later.

- It was either down-right impossible or very difficult, to get accurate information out of Darwin because communication was either cut or sketchy at best. Sadly, the Darwin Post Office, the primary source of communication with the rest of Australia, suffered a direct hit on the 19 February killing 10 civilians, all of whom had volunteered to remain in Darwin despite the growing threat of attack.

(Bank of New South Wales after air raid, 1942: Northern Territory Library Darwin Bombing Collection PH0808/0021.)

We remember

The community is invited to take part in the Bombing of Darwin Day program of events to commemorate those who courageously defended our country, those who selflessly helped others, those who dealt with the aftermath, and those who lost their lives.

We lost

After remaining virtually untouched by foreign conflict, war had finally come to Australia's shores. The Bombing of Darwin left hundreds of servicemen and civilians dead, countless others injured and a significant toll on Darwin's infrastructure.

The attacks which began in Northern Australia on 19 February 1942 continued for 21 months.

We unite

The Bombing of Darwin was a defining moment in Australia's history and highlighted the tenacity and spirit of those who bravely fought against the attacks. The community rallied around the broken families of those impacted and worked together to rebuild after the unprecedented attacks.

On 7 December 2011, the Governor General of the Commonwealth of Australia, declared 19 February as a national day of observance to be known as Bombing of Darwin Day.

We commemorate

Our National Day of Observance is a time to learn about the significance of the Bombing of Darwin in Australia's military history, to understand the sacrifices of those who contributed to the defence of Australia during World War II, and to reflect on the value of peace.

A defining moment in Australia’s history

Darwin's defenders were caught unawares when 188 aircraft from the Imperial Japanese Nave appeared from the south-east at 9:58am on 19 February 1942.

The attack was the first of at least 64 air raids on the Top End of Australia, which continued until 12 November 1943.

Despite its severity and impact, the Bombing of Darwin and the war fought over Northern Australia is often overshadowed by subsequent events in our nation's history.

Remnants of WWII are still visible at many locations across Darwin, Katherine and Adelaide River. These sites offer visitors a chance to pay homage to both the heroes who fought on the frontline and the Territory’s multicultural community affected by the bombing raids. Asian, European and Indigenous people worked alongside the allied servicemen as Darwin was attacked over an 18 month period.

The devastation suffered by Territorian families was profound. The evacuees who returned and the wider community came together to rebuild Darwin after the war, and many stories of tragedy and survival have been shared during these years.

No event in history has highlighted the tenacity, resilience, and spirit of those living in the Territory, quite as profoundly as the Bombing of Darwin.

Timeline

- 08 December 1941

-

Japanese Imperial Forces attacked Kota Bahru and Pearl Harbour (7 December local time in Hawaii).

One hour after the attack by the Japanese at Pearl Harbour, Prime Minister John Curtin of Australia declared that "from one hour ago, Australia has been at war with the Japanese Empire”.

- 10 December 1941

-

British warships, Prince of Wales and Repulse, are attacked and destroyed off Malaya.

- 16 December 1941

-

Evacuation of non-essential civilian women and children from Darwin ordered. By 18 February more than 2,000 people were evacuated. The normal civilian population during that era was around 5,000.

- 15 February 1942

-

The British fortress of Singapore falls to Japanese forces who then prepare to invade Timor on 20 February.

An Allied convoy leaves Darwin to reinforce Timor.

- 16 February 1942

-

Heavy air attack forces the Allied convoy to turn back and return to Darwin.

- 18 February 1942

-

The Allied convoy arrives back in Darwin.

- 19 February 1942

-

8.00am Japanese aircraft (36 Zero Fighters, 71 Dive Bombers and 81 Level Bombers) commence their mission.

9.15am Japanese aircraft are seen over Melville Island and then again over Bathurst Island at 9.35am. Warnings are sent by wireless but are misinterpreted. Allied Catalina aircraft are attacked and Bathurst Island airstrip is strafed.

9.58am Japanese aircraft drop the first bombs and commence their attack on Darwin Harbour and the city surrounds.

12noon Second wave of 54 Bombers attack the Darwin RAAF Base area.

More information

For further information contact the Community Events Coordinator

Media Resources

Uncompressed and compressed footage reels of the Bombing of Darwin Commemorative Service on 19 February will be available from 2pm ACST.